Deconstructing M1: The Most Liquid Forms of Money

M1, a key component of the broader money supply m1 and m2, represents the most liquid forms of money in an economy. Understanding its composition is crucial for analyzing economic activity. The primary components of M1 include currency in circulation, demand deposits, traveler’s checks, and other checkable deposits. Currency in circulation refers to physical money—the banknotes and coins—held by the public. It facilitates everyday transactions and serves as a direct medium of exchange. Demand deposits are funds held in checking accounts at commercial banks. These deposits are readily accessible and can be withdrawn or transferred on demand, typically through checks, debit cards, or electronic transfers. As part of money supply m1 and m2, demand deposits play a vital role in facilitating payments between individuals and businesses.

Traveler’s checks, while less common today due to the rise of electronic payment methods, are prepaid instruments that can be used for purchases. They offer a secure alternative to carrying large amounts of cash, particularly during travel. Other checkable deposits encompass various interest-bearing checking accounts and negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts offered by financial institutions. These accounts allow depositors to earn interest on their balances while retaining the ability to write checks or make electronic transfers. The defining characteristic of all M1 components is their high degree of liquidity. Liquidity refers to the ease and speed with which an asset can be converted into cash without significant loss of value. M1 assets can be readily used for transactions, making them an essential part of the money supply m1 and m2 and a reliable indicator of immediate purchasing power within the economy.

Each component of M1 serves a distinct role in facilitating economic activity. Currency in circulation supports smaller, everyday transactions where electronic payments may not be practical. Demand deposits and other checkable deposits streamline larger transactions and provide a convenient means of managing funds. Traveler’s checks cater to specific needs related to travel and security. The aggregate amount of money supply m1 and m2 is closely monitored by central banks and economists as it provides insights into the level of transactional activity and potential inflationary pressures in the economy. An increase in M1 may indicate increased spending and economic growth, while a decrease could signal a contraction in economic activity. Thus, M1 serves as a critical benchmark for assessing the short-term health and direction of the economy and plays an integral role in the overall dynamics of the money supply m1 and m2.

What Constitutes M2? Expanding the Definition of Money Supply

M2 builds upon the foundation of M1, expanding the definition of the money supply. It encompasses all the components of M1, which represents the most liquid forms of money, and adds other “near monies.” These near monies are not as immediately accessible as cash or checking accounts but can be readily converted into cash. Therefore, understanding the money supply m1 and m2 relationship is essential for economic analysis.

Specifically, M2 includes savings deposits, which are accounts where money is stored for future use and typically earn interest. Money market deposit accounts (MMDAs) are another component. MMDAs offer features similar to savings accounts but may have limited check-writing abilities. Small-denomination time deposits, also known as certificates of deposit (CDs), are also part of M2. These are deposits held for a fixed period and have penalties for early withdrawal. Defining this broader scope of the money supply m1 and m2 allows economists and policymakers to gain a more comprehensive view of the total amount of money available in the economy. This more comprehensive view helps when assessing economic conditions. The distinction between M1 and M2 allows for a more nuanced analysis of the money supply m1 and m2 and its potential impact on economic activity.

The purpose of defining M2 is to capture a wider range of assets that serve as stores of value and can be easily converted into transactionary money. By including these less liquid components, M2 provides a more stable and comprehensive measure of the money supply m1 and m2. This broader perspective is particularly useful when analyzing long-term trends and assessing the potential for future spending and investment. Furthermore, changes in M2 can provide insights into consumer confidence and saving behavior. Shifts between M1 and M2 components might signal changes in economic sentiment. While M1 focuses on the money readily available for transactions, M2 offers a broader view of the overall money supply m1 and m2. This view includes funds that could potentially be activated for spending in the near future. Understanding both M1 and M2 is crucial for effective monetary policy and economic forecasting.

How to Interpret Changes in M1 and M2: Indicators of Economic Health

Changes in the money supply m1 and m2 can serve as valuable indicators of overall economic health and potential inflationary pressures. Monitoring the growth rates of money supply m1 and m2 provides insights into the level of liquidity in the economy. A rapid increase in the money supply m1 and m2 might suggest that the economy is expanding. This expansion can lead to increased spending and investment. Conversely, a slow or declining money supply m1 and m2 could signal an economic slowdown or recession.

The relationship between money supply m1 and m2 growth, interest rates, and economic growth is complex. When the money supply m1 and m2 increases faster than the economy’s output, it can lead to inflation. This happens because there is more money chasing the same amount of goods and services. To combat inflation, central banks often raise interest rates. Higher interest rates can slow down borrowing and spending. This action, in turn, can moderate economic growth. Lowering interest rates can stimulate borrowing and investment, potentially boosting economic growth.

Changes in money supply m1 and m2 can significantly impact consumer spending and investment decisions. An increase in the money supply m1 and m2, coupled with low-interest rates, can encourage consumers to borrow and spend more. This increase in consumer demand can drive economic growth. Similarly, businesses may be more inclined to invest in new projects and expand their operations when the money supply m1 and m2 is abundant and borrowing costs are low. However, if the money supply m1 and m2 grows too rapidly, it can create asset bubbles and unsustainable economic booms. Conversely, a contraction in the money supply m1 and m2 can lead to decreased spending and investment. It is crucial for policymakers to carefully monitor and manage the money supply m1 and m2 to maintain a stable and healthy economy. The balance between stimulating growth and controlling inflation is a key consideration.

The Federal Reserve’s Role in Managing Monetary Aggregates

The Federal Reserve, acting as the central bank, exerts considerable influence over the money supply m1 and m2 through its monetary policy tools. These tools are designed to manage economic activity and inflation by controlling the availability of money and credit in the economy. The primary tools employed include open market operations, the reserve requirement, and the discount rate. These mechanisms directly impact the money supply m1 and m2.

Open market operations involve the buying and selling of U.S. government securities in the open market. When the Federal Reserve purchases securities, it injects money into the banking system, increasing the reserves available to banks. This, in turn, enables banks to expand lending activity, thereby increasing the money supply m1 and m2. Conversely, when the Federal Reserve sells securities, it withdraws money from the banking system, reducing bank reserves and contracting the money supply m1 and m2. This tool is frequently used to fine-tune the money supply m1 and m2 and maintain desired interest rate levels.

The reserve requirement is the fraction of a bank’s deposits that it must hold in reserve, either in its account at the Federal Reserve or as vault cash. By increasing the reserve requirement, the Federal Reserve forces banks to hold a larger portion of their deposits in reserve, reducing the amount of money available for lending and decreasing the money supply m1 and m2. Decreasing the reserve requirement allows banks to lend more, thus expanding the money supply m1 and m2. Changes to the reserve requirement are less frequently used due to their potentially disruptive effects on bank operations. The discount rate is the interest rate at which commercial banks can borrow money directly from the Federal Reserve. A lower discount rate encourages banks to borrow more, increasing the money supply m1 and m2. A higher discount rate discourages borrowing and reduces the money supply m1 and m2. This rate serves as another tool to influence short-term interest rates and manage the overall money supply m1 and m2. By strategically employing these tools, the Federal Reserve aims to foster economic stability, control inflation, and promote sustainable economic growth, all while closely monitoring the effects on the money supply m1 and m2.

Distinguishing Between M0, M1, M2, and M3: A Complete Hierarchy

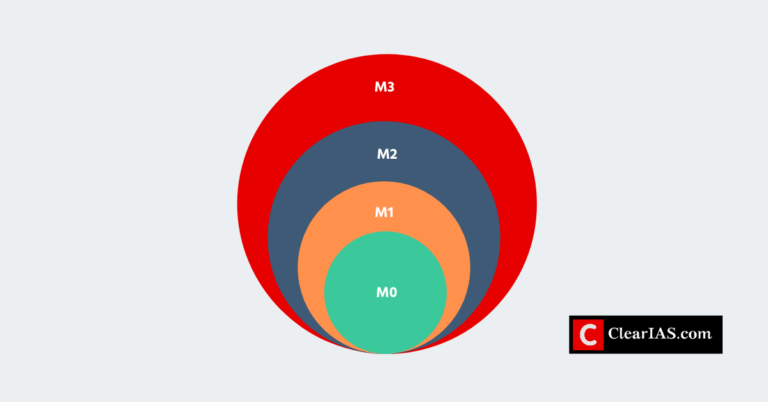

Understanding the broader context of money supply m1 and m2 requires examining the complete hierarchy of monetary aggregates. M0, also known as the monetary base, represents the most basic measure of money supply. It comprises physical currency in circulation and commercial banks’ reserves held at the central bank. M1, a narrower measure of money supply, builds upon M0 by adding highly liquid components like demand deposits and checkable accounts. These are funds readily accessible for transactions. M2 then encompasses M1 plus less liquid near monies such as savings deposits and money market accounts. These assets can be converted to cash relatively easily, but they aren’t used directly for most transactions. The relationship between these three – M0, M1, and M2 – demonstrates a progression from the most liquid to less liquid forms of money.

Historically, M3, a broader measure than M2, also existed. It included large-denomination time deposits, institutional money market funds, and other less liquid assets. However, many central banks, including the Federal Reserve, have discontinued publishing M3 data. This decision reflects a belief that M1 and M2 offer sufficient insight into the money supply’s impact on the economy. The rationale is that M3’s components are less directly relevant to consumer spending and inflation and they are less responsive to monetary policy tools. Focusing on money supply m1 and m2 allows for a clearer picture of the most relevant drivers of economic activity.

The emphasis on M1 and M2 in economic analysis stems from their strong correlation with overall economic activity and inflation. Their components directly reflect transactions and spending patterns. Economists and policymakers closely monitor changes in M1 and M2 to gauge the effectiveness of monetary policies and to forecast future economic trends. While other metrics exist, M1 and M2 remain the most widely used and closely watched indicators of the money supply. Their accessibility and direct relationship to consumer behavior make them invaluable tools in understanding the complexities of the modern economy and managing monetary policy effectively. The money supply m1 and m2 data helps monitor economic health and stability.

Real-World Examples: Analyzing Recent Trends in Money Supply M1 and M2

Understanding recent trends in money supply M1 and M2 offers valuable insights into economic health. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted these metrics. In the initial phases, unprecedented government stimulus programs and the Federal Reserve’s expansionary monetary policies led to a dramatic surge in both M1 and M2. This rapid increase reflected the injection of liquidity into the financial system to support businesses and individuals. The expansion of money supply M1 and M2 aimed to mitigate the economic downturn and prevent a deeper crisis. The increase in M2 was particularly pronounced due to the growth in savings deposits and money market accounts, as individuals and businesses sought safe havens for their cash. This period demonstrates the direct relationship between government intervention and the rapid changes in the money supply M1 and M2.

Subsequently, as the economy began to recover, the growth rate of M1 and M2 moderated. However, the levels remained elevated compared to pre-pandemic times. This reflects a lingering impact of the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus. The sustained increase in M2, in particular, points to a shift in household savings behavior. Concerns about future economic uncertainty might be contributing to higher savings rates and, consequently, higher levels of M2. Analyzing money supply M1 and M2 alongside other economic indicators, such as inflation, consumer spending, and employment, provides a more complete picture of the economic landscape. Changes in velocity of money must also be considered when interpreting these data. The interplay between these factors highlights the complexities of interpreting money supply M1 and M2 trends.

A chart depicting the growth of M1 and M2 from, say, 2019 to the present would visually demonstrate these trends. Such a chart would clearly show the sharp increase during the pandemic, the subsequent moderation, and the current elevated levels relative to pre-pandemic norms. This visual representation would enhance understanding of the dynamics of money supply M1 and M2 and its implications for the overall economy. The interplay between monetary policy actions and changes in M1 and M2 underscores the importance of carefully monitoring these crucial economic indicators. Careful analysis of the money supply M1 and M2 is essential for informed economic decision-making.

The Velocity of Money: How Quickly is Money Circulating?

The velocity of money measures how quickly money changes hands in an economy. It’s a crucial concept when analyzing money supply M1 and M2, because it shows how effectively the existing money supply fuels economic activity. A higher velocity means each dollar is used more frequently for transactions, boosting overall economic output. Conversely, a lower velocity suggests money is circulating more slowly, potentially hindering economic growth. Understanding velocity is essential because it impacts inflation and economic expansion, even when the money supply itself remains relatively stable. Changes in the money supply m1 and m2 do not tell the whole story; velocity is an important complementary factor.

Several factors influence the velocity of money. Interest rates play a significant role. Higher interest rates incentivize saving, reducing the velocity of money as people hold onto their funds instead of spending or investing them. Consumer confidence also matters. During periods of economic uncertainty, consumers tend to save more, leading to a slower velocity. Technological advancements, like the widespread adoption of digital payment systems, can increase the velocity of money by facilitating faster and more frequent transactions. Government policies, particularly fiscal and monetary policies, also have an effect. For example, expansionary fiscal policies can increase spending and boost velocity, while contractionary policies might have the opposite effect. The interplay between the money supply m1 and m2 and velocity is complex, but essential for economists and policymakers seeking to understand and manage economic conditions.

The relationship between money supply m1 and m2 and velocity is expressed in the equation of exchange: MV = PQ, where M represents the money supply, V represents the velocity of money, P represents the price level, and Q represents the quantity of goods and services. This equation highlights how changes in the money supply, velocity, or both can influence the overall price level and economic output. Analyzing the velocity of money alongside the money supply m1 and m2 provides a more comprehensive picture of the economy’s health than simply looking at money supply figures in isolation. This holistic view allows for a more nuanced understanding of economic trends and potential policy responses. Tracking changes in both the money supply and velocity offers a more accurate reflection of the dynamics of the economy and is crucial for effective economic management.

M1 and M2 vs. Alternative Money Supply Metrics: Which Matters Most?

While M1 and M2 represent the most commonly used measures of money supply, alternative metrics exist. These include broader aggregates encompassing less liquid assets, such as M3 (though its use has declined in many countries) and various monetary base measures like M0. Each metric offers a different perspective on the money supply. M0, for instance, focuses on the most readily available money created by the central bank. Broader aggregates, on the other hand, include assets that are less readily convertible to cash, providing a broader picture of financial liquidity in the economy. The choice of which metric to use depends on the specific economic question being addressed. For example, analyzing short-term liquidity might favor M1, while examining long-term investment potential might necessitate considering broader measures. The continued relevance of money supply M1 and M2 stems from their focus on readily available funds for transactions, providing a key insight into consumer spending and short-term economic activity. However, these measures might not fully capture the complexities of the modern financial landscape, especially given the growth of digital currencies and financial innovations that might blur the traditional lines between different asset classes. A more nuanced understanding of money supply, therefore, often involves considering these alternative metrics alongside M1 and M2.

The advantages of using M1 and M2 for assessing money supply are their simplicity, historical data availability, and clear relationship to economic activity. Economists and policymakers extensively use these measures to monitor short-term economic trends and adjust monetary policies accordingly. The ease of understanding and the readily available data make these metrics crucial for quick economic assessments. Their limitations lie in their potential to underrepresent the total amount of money actively circulating in the modern, increasingly digital, economy. The rise of digital currencies and other forms of electronic payments makes it harder for traditional measures like M1 and M2 to fully encompass the breadth of money supply. Furthermore, changes in financial regulations and technological advancements could impact the relationship between money supply M1 and M2 and economic activity, highlighting the need for continuous evaluation and potential refinement of these measures.

Despite these criticisms, money supply M1 and M2 remain highly relevant. They provide a relatively simple and widely understood framework for assessing money supply. Their long history of data availability allows for robust time-series analysis, facilitating informed economic predictions and policy decisions. While alternative measures may capture additional aspects of the financial landscape, the immediate and tangible connection between M1 and M2 and consumer spending and overall economic activity makes them essential tools for economists and policymakers, and their importance is unlikely to diminish significantly in the near future. The debate regarding the ideal money supply metric continues, with ongoing research exploring the potential benefits and shortcomings of various approaches to measuring the money supply in an increasingly complex global financial system. The ongoing refinement of methodologies and the exploration of supplementary metrics will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of money supply dynamics. The focus on money supply M1 and M2, however, remains a cornerstone of macroeconomic analysis and monetary policy decisions.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/money-supply-4192738-a002986b86714240b0c6b46453171588.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/m2-Final-2df63feeb3174bafaf1eb8818803c4f7.jpg)