Differentiating Between Flow and Stock Variables: An Introductory Guide

Understanding the distinction between a flow variable vs stock variable is crucial in economics. These concepts help us analyze economic phenomena accurately. A flow variable is measured over a specific period. Think of it as something that moves or changes over time. In contrast, a stock variable is measured at a particular point in time. It represents a quantity that exists at that moment.

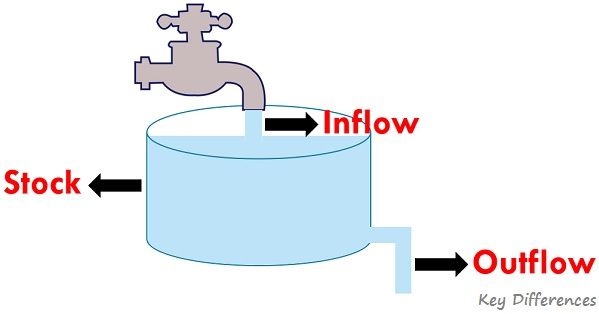

To grasp this, let’s consider some relatable examples. Imagine water flowing from a tap into a bathtub. The rate at which water enters the tub (liters per minute) is a flow variable vs stock variable. The amount of water in the tub at any given moment is a stock variable. Similarly, consider your daily commute. The number of miles you drive each day is a flow. The total mileage on your car’s odometer at this instant is a stock. These examples highlight the difference between measurement over time and measurement at a specific point.

Now, let’s translate these concepts into economic terms. Income is a prime example of a flow variable vs stock variable. You earn income over a period, such as a week, month, or year. On the other hand, your wealth represents a stock variable. It’s the total value of your assets, like savings, investments, and property, at a specific moment. The flow of income can increase your stock of wealth if you save a portion of it. Recognizing the flow variable vs stock variable nature of economic data is the first step toward sound economic reasoning.

How to Recognize Flows: Examples Across Various Disciplines

Flow variables are fundamental in economics, representing quantities measured over a specific period. Understanding the “flow variable vs stock variable” distinction requires recognizing their time-bound nature. Unlike stock variables, which capture a value at a single point in time, flow variables accumulate or diminish over an interval. This section elaborates on flow variables, providing diverse examples from various fields to solidify your comprehension.

In finance, income is a prime example of a flow variable. It’s typically measured as income per month or income per year, clearly defining the period over which it is earned. Investment also falls under flow variables, representing the amount of capital injected into a project or economy over a certain period. Similarly, expenses, whether personal or business-related, are measured as spending per day, week, or month. These examples highlight the importance of the time dimension when analyzing flow variables. Even outside of economics, we can observe flow variables. Consider the flow of a river, measured in cubic meters per second or gallons per minute. This exemplifies how the quantity of water passing a certain point is tracked over time. Another “flow variable vs stock variable” example from everyday life, imagine water filling a bathtub; the rate at which the water enters the tub is a flow variable.

To further clarify, consider units of measurement. Flow variables are always expressed with a time component. Examples include GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per quarter or year, the number of new houses built per month, or the amount of oil extracted per day. These units of measurement reinforce the time-dependent nature of flows, further distinguishing “flow variable vs stock variable”. Grasping this time-bound aspect is crucial for accurate economic analysis. Recognizing flow variables across diverse contexts, from financial statements to natural phenomena, strengthens your ability to differentiate them from stock variables and apply them effectively in various analytical scenarios. The concept of “flow variable vs stock variable” becomes clearer with each practical example, enabling you to better interpret economic data and make informed decisions.

Grasping Stock Variables: Illustrative Scenarios and Applications

Stock variables represent a quantity measured at a specific point in time. Unlike a flow variable vs stock variable, which is measured over an interval, a stock offers a snapshot of a particular attribute. Think of it as taking a photograph – it captures the situation at that exact moment. Examples of stock variables are widespread and crucial in understanding economic conditions. Wealth, for instance, is a stock variable. It represents the total value of assets owned by an individual, household, or nation at a given time. This could include savings, property, and investments. National debt is another important stock variable, showing the total accumulated debt of a government at a particular point.

Inventory is a common example used in business and economics as a flow variable vs stock variable. It refers to the quantity of goods a company has on hand at a specific time, ready to be sold or used in production. Population, the number of people residing in a specific area at a given time, is also a stock variable. These examples highlight the importance of the ‘point-in-time’ aspect. Understanding the current level of these stocks provides valuable insights into the state of an economy or a business.

The magnitude of a flow variable vs stock variable can be altered by flows. To illustrate, wealth (a stock) is increased by savings (a flow) and decreased by expenditures exceeding income (a negative flow). Similarly, a company’s inventory stock increases with production (inflow) and decreases with sales (outflow). National debt (a stock) increases with government deficits (a flow) and decreases with government surpluses (a flow). The interplay between flows and stocks is critical. It’s essential for analysts and policymakers to understand how flows contribute to changes in stocks over time to inform economic analysis and develop effective strategies. Recognizing the difference between a flow variable vs stock variable enables a more accurate assessment of economic situations and trends.

The Interplay Between Flows and Stocks: Dynamic Relationships

The relationship between flow variable vs stock variable is a fundamental concept in economics. Flow variables directly impact stock variables, causing them to change over time. Understanding this interaction is crucial for analyzing economic phenomena and predicting future trends. A flow variable is measured over a specific period, whereas a stock variable is measured at a particular point in time. This temporal difference is key to understanding their relationship.

Consider investment as a flow and capital as a stock. Investment, measured as dollars per year, represents the flow of new capital into an economy. This investment flow increases the capital stock, which is the total value of equipment, buildings, and infrastructure at a given point. Conversely, depreciation, another flow (a negative one), decreases the capital stock. Similarly, consider savings as a flow and wealth as a stock variable. Savings, the portion of income not spent, is measured over time (e.g., monthly or annually). This flow of savings accumulates and contributes to an individual’s or a nation’s wealth, which is the total value of assets at a specific moment. Consumption, representing spending, is a flow variable that reduces wealth. These examples highlight how flow variables are the driving forces behind changes in stock variables, and in this context flow variable vs stock variable is critical.

Feedback loops can also exist between flow variable vs stock variable. For instance, an increase in the capital stock can lead to increased production and economic growth. This growth, in turn, generates higher incomes, leading to higher savings flows and further increases in the capital stock. Another example is government debt. Government spending exceeding tax revenue creates a deficit, a flow variable that adds to the national debt, a stock variable. A large national debt can then lead to higher interest payments, further increasing the deficit and creating a feedback loop. Recognizing these dynamic relationships and feedback mechanisms is essential for effective economic analysis and policymaking. Analyzing how flow variable vs stock variable interact allows for a more complete understanding of economic processes.

Impact on Economic Analysis: Significance for Economists

Understanding the difference between a flow variable vs stock variable is vital for economists and policymakers. Misinterpreting these concepts can lead to flawed economic analysis and ineffective policies. A flow variable is measured over a period, while a stock variable is measured at a specific point in time. Recognizing this distinction is not merely academic; it has real-world consequences.

For example, consider government spending and national debt. Government spending is a flow variable, representing the amount of money a government spends over a given period, such as a year. National debt, on the other hand, is a stock variable, representing the total accumulation of past deficits at a specific point in time. If policymakers focus solely on reducing government spending (a flow) without considering the existing national debt (a stock), they may implement austerity measures that harm economic growth. Similarly, increasing government spending without a strategy to manage the debt can lead to unsustainable levels of indebtedness. Accurate economic analysis requires careful consideration of both flow variable vs stock variable.

Another crucial area where this distinction matters is in monetary policy. Central banks often target inflation, which is a flow variable representing the rate at which prices increase over time. To control inflation, they might adjust interest rates, influencing the flow of credit in the economy. However, they must also consider the level of household and corporate debt, which are stock variables. High levels of debt can make the economy more sensitive to interest rate changes, potentially leading to unintended consequences. A proper understanding of flow variable vs stock variable enables economists to build more accurate models and advise policymakers effectively. Failing to distinguish between flow variable vs stock variable can result in inaccurate forecasts and poor decision-making. This can have far-reaching effects on economic stability and growth, illustrating the fundamental importance of grasping these concepts.

Real-World Applications: Analyzing Economic Scenarios

To illustrate the practical significance of differentiating between flow and stock variables, consider several real-world economic scenarios. These examples will showcase how a clear understanding of the difference between a flow variable vs stock variable can lead to more informed analysis and decision-making. One compelling example is the analysis of the housing market, which is a field where distinguishing between these concepts is essential.

In the housing market, the existing housing supply represents a stock variable, measured at a specific point in time. It’s the total number of houses available for sale or rent at any given moment. New construction, on the other hand, is a flow variable. It represents the rate at which new houses are being built and added to the housing stock over a period, such as a month or a year. Understanding this distinction is crucial for predicting price movements and market equilibrium. If the flow of new construction is less than the demand for housing, the housing stock will decrease relative to demand, potentially leading to price increases. Conversely, if the flow of new construction exceeds demand, the housing stock will increase, potentially leading to price decreases or a stabilization of prices. Another important example is understanding government debt dynamics, the government deficit is a flow variable, representing the difference between government spending and revenue over a period. The national debt, however, is a stock variable, which accumulates over time as a result of past deficits (flows). Misunderstanding this relationship can lead to flawed fiscal policy decisions. For instance, a short-term focus on reducing the deficit (a flow) without considering the long-term impact on the national debt (a stock) can have unintended consequences. Government spending (a flow variable) directly influences the national debt (a stock variable) over time, impacting economic stability and future generations. A further example can be found in the performance assessment of a firm. Revenue (sales) is a flow variable, representing the income generated by the company over a period. Assets, such as buildings, equipment, and cash reserves, are stock variables, measured at a specific point in time. Investors and analysts use both flow and stock variables to assess a firm’s financial health and future prospects. A company with high revenue (flow) but low assets (stock) may be more vulnerable to economic downturns than a company with a more balanced profile. Understanding the interplay between a flow variable vs stock variable is key for comprehensive financial analysis.

These examples highlight the need to carefully consider the time dimension and the point-in-time nature of economic variables. Failing to do so can lead to inaccurate assessments and poor decision-making. By recognizing the difference between a flow variable vs stock variable and their interrelationships, economists, policymakers, and investors can gain a more nuanced understanding of the economy and make more informed choices. A better knowledge of flow variable vs stock variable is then key to understanding economics.

Common Misconceptions: Avoiding Errors in Interpretation

One of the most frequent errors in economic understanding involves confusing flow variable vs stock variable concepts. Savings and wealth provide a prime example. Savings represents a flow variable, measured over a period, such as monthly or annually. It reflects the portion of income not spent on consumption. Wealth, conversely, is a stock variable. It is measured at a specific point in time and represents the total value of accumulated assets, including savings, investments, and property.

Another common pitfall lies in mistaking income for capital. Income, a flow variable, is earned over time. Capital, a stock variable, represents accumulated resources or assets at a specific moment. Similarly, confusing deficit and debt is a common error. The deficit, a flow variable, measures the difference between government spending and revenue over a period. The national debt, a stock variable, represents the total accumulation of past deficits.

To avoid these misinterpretations concerning flow variable vs stock variable, pay careful attention to the time dimension. Flow variables always have a time component (per day, per month, per year), while stock variables are snapshots at a particular point. When analyzing economic data, ensure a clear understanding of whether the variable represents a rate of change over time or a quantity at a specific moment. This distinction is crucial for accurate economic analysis and informed decision-making. Understanding the distinction between flow variable vs stock variable prevents flawed analysis. Recognizing the difference between flow variable vs stock variable is essential for sound economic reasoning.

Future Considerations: Evolution and Relevance in Modern Economics

The concepts of flow variable vs stock variable maintain evolving relevance within modern economic modeling. These fundamental distinctions are vital for understanding economic dynamics and forecasting future trends. As economies become more complex, so too do the models used to analyze them.

Advanced macroeconomic models increasingly rely on the careful differentiation between flow variable vs stock variable to simulate economic behavior accurately. For example, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models incorporate flow and stock variables to analyze business cycles and the effects of policy interventions. Understanding how these variables interact is crucial for assessing the stability and growth prospects of an economy. Moreover, flow variable vs stock variable analysis plays a key role in assessing sustainability of economic policies in the long term. Stock-flow consistent (SFC) models represent an even more sophisticated approach. SFC models ensure that all flows and stocks within the model are properly accounted for, creating a closed-loop system. This approach is particularly useful for analyzing the relationships between different sectors of the economy, such as the government, households, and firms. SFC models are valuable tools for understanding financial stability, debt dynamics, and the potential for systemic risk. The study of flow variable vs stock variable is essential for economists and researchers looking to develop a deeper understanding of economic systems.

Further exploration in this field includes investigating the impact of technological advancements on flow and stock relationships. For example, the increasing importance of intangible assets (a stock) and the flow of information are reshaping traditional economic models. Researchers are also examining how environmental flows (such as carbon emissions) affect environmental stocks (such as atmospheric carbon concentration) and the implications for sustainable development. By continuing to refine our understanding of flow variable vs stock variable and their interactions, economists can develop more effective policies to promote economic stability, growth, and sustainability. These concepts provide a foundation for analyzing complex economic challenges and informing policy decisions in an ever-changing world. The flow variable vs stock variable framework remains a cornerstone of economic analysis, offering a lens through which to understand and shape the future of our economies.